Sea Urchins, Chick Embryos, and Fruit Flies: Oh, My!

With science in my major title, I’m no stranger to STEM courses at Arcadia. Typically in scientific illustration, you will take a couple science classes per year, and going into my senior year fall, I only needed one 300-level to round them out. With a couple different options, I went with Developmental Biology, a course offered every other year, and it’s been one of the most fascinating courses I have taken yet.

Developmental biology is the study of the processes of cell differentiation, tissue morphogenesis, and organogenesis in animals. Essentially, the course is a study on how embryos develop into full beings and the mechanisms for how this happens. Since the topic is deeply complex, this science looks at a few different creatures called “model organisms” that have provided insight into how different developmental processes occur. In our weekly labs, we would then get to study these organisms and processes for ourselves to better understand what we had learned!

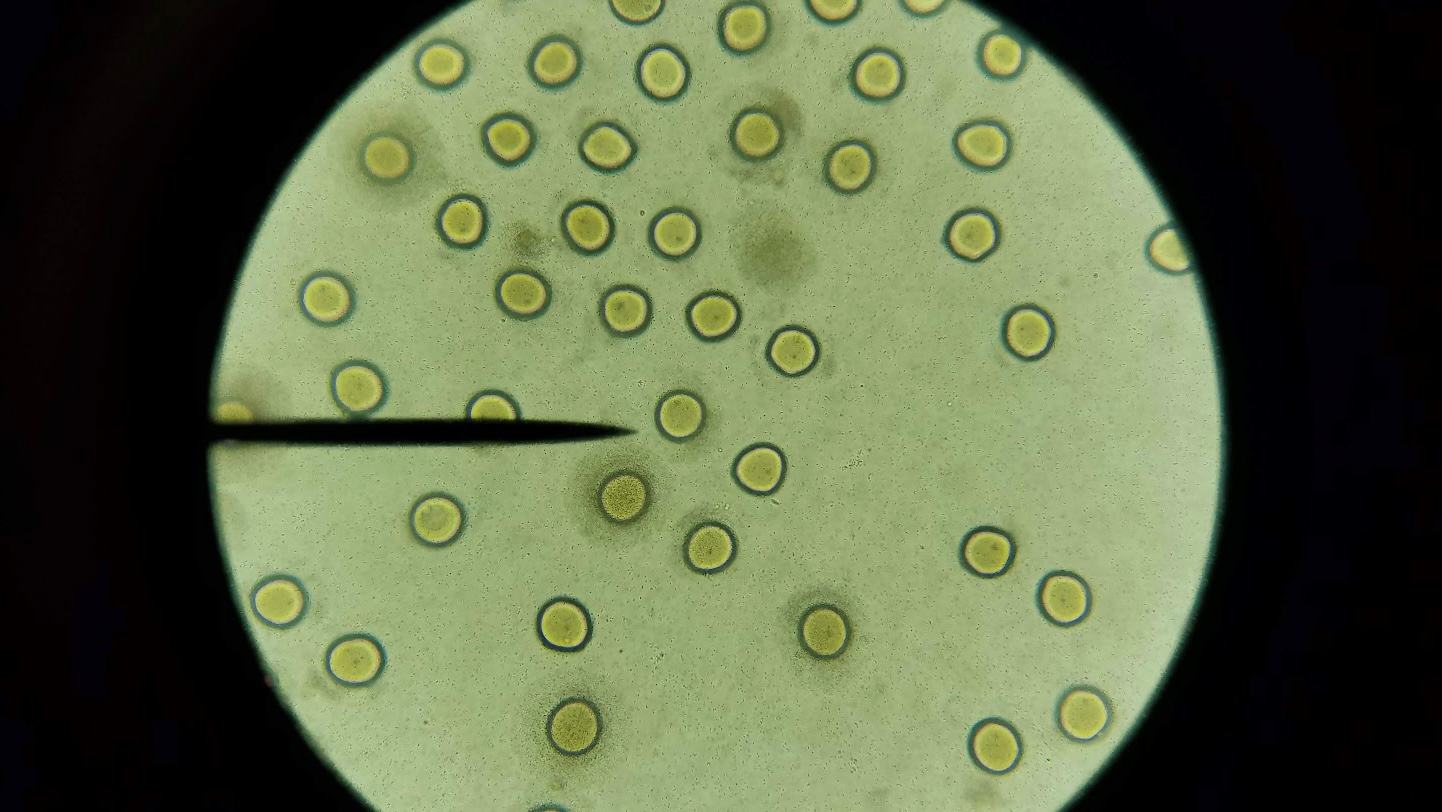

In one of our earliest labs, we had the task of fertilizing sea urchins so we could observe the fertilization process. We were given one sea urchin per lab group at random (and not knowing whether it was male or female), and once we did a chemical injection, the urchin would either produce sperm or eggs. Our urchin was female, so we borrowed some sperm from the table next to us and, in a separate dish, combined the sperm and the eggs and popped it under the microscope. Though it sounded like a strange task, it turned out to be fascinating to see the process and understand what was happening!

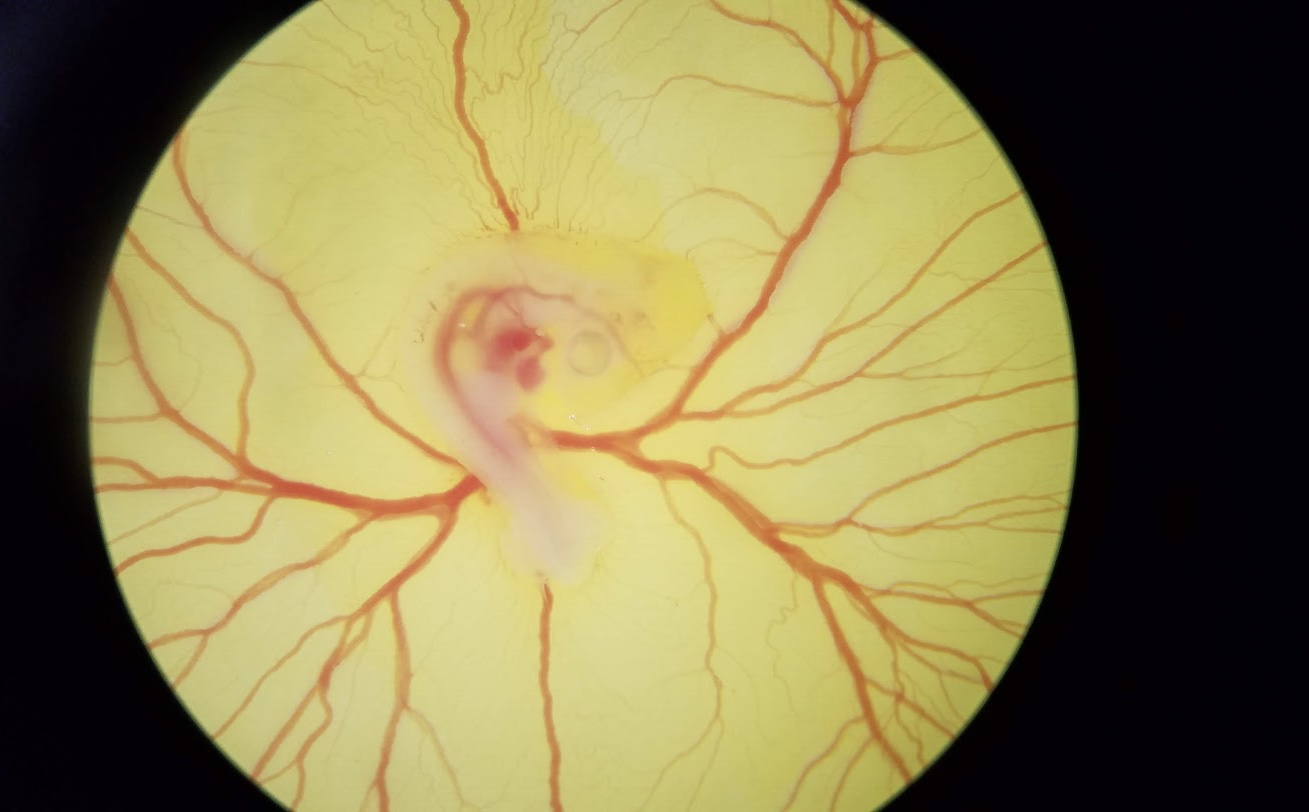

In another lab, we got to observe stages of chick embryos at different hours of development. Since chicks undergo external development in an egg (as opposed to internal development in the mother!). This makes them a great model for seeing the process of development. Our lab groups observed chick embryos at 48 hours into development, 72 hours into development, and 96 hours into development. Though it was only a few short hours in difference, there were major changes between each- in the earliest embryo, we could only see a few structures starting to form. At 72 hours, we could clearly see the notochord, parts of the brain, and other facial and limb structures forming. At 96 hours, most of the embryo was formed and we could even see the heart beating.

Our current lab assignment for the rest of the semester is a collaboration with three other universities across the country to study a fruit fly mutation and the role it plays in various processes like meiosis, DNA repair, and development. Our class specifically is studying how this loss of function gene affects female fertility and development. This past week, we dissected fruit fly ovaries from both mutated flies and normal flies, and are waiting for them to be fluorescently stained so we can observe the differences next week.

Developmental biology gives the opportunity to observe the processes alongside the learning firsthand, and learning something so interesting for my final science course at Arcadia has made my senior year that much better.