Whether you’ve had senioritis and have been counting down the days until your last exam, or just the mention of the Real World is enough to make you break out in a cold sweat, college ends for everyone eventually. Though most leave higher education to pursue a career in the workforce, many opt instead to remain students for a little longer in pursuit of an advanced degree.

According to 2018 data from the United States Census Bureau, the number of people with a master’s degree has doubled from 10.4 million to 21 billion. While graduate school is a big personal and financial commitment and not for everyone, my goal has been to work in academia, something that requires additional degrees. My own application process to English master’s programs may not be the same as those for other fields, but hopefully sharing it might help you decide if graduate school is for you and how to move forward if you choose.

1. Determine why you want to go to graduate school.

One of my professors once said that you shouldn’t go to graduate school simply because you don’t know what else to do with your life and are avoiding making decisions. After all, graduate school is not only academically demanding, but also can be a major economic investment if you don’t find yourself fully funded. Moreover, you lose a year or more of income that you could have been making if you had worked full time instead.

It is important, then, to have a plan in place. Be realistic and ask yourself if getting a master’s degree in your field has the appropriate return on investment. In my own case, I was told that enjoying writing and reading was not sufficient to sustain me through a graduate program, let alone get me accepted in the first place. Knowing that I can’t really picture myself outside of a classroom setting affirmed to me that this was the path I needed to take, despite the fact jobs in higher education are not always readily available and high-paying.

Writing review with Associate Professor of English Dr. Liz Vogel.

2. Forge your academic identity during your final semesters.

In your early twenties, it can seem daunting thinking you have to decide what type of research you want to commit to for the rest of your academic life. Be reassured that the scholarship you do as an undergraduate is not a ball and chain around the ankles, and you will have flexibility to explore other areas of intellectual inquiry. That said, it’s advisable to tailor the activities and academic assignments of your later college years to reflect what you may want to work on in the future.

In my case, I knew that I really enjoyed writing on gender, particularly constructions of masculinity, and probably would want to continue doing so in graduate school. Therefore, I made sure the bulk of my thesis and other papers involved this topic, and picked up a minor in Gender and Sexuality Studies to demonstrate to potential schools that I had a strong theoretical background in gender theory. To already possess a keen sense of what you want to study is strong evidence that you are a rising academic with active research questions in mind.

In your twenties, it can seem daunting thinking you have to decide what type of research you want to commit to for the rest of your academic life. Be reassured that the scholarship you do as an undergraduate is not a ball and chain around the ankles.

– Jess Derr

3. Do your research.

Once you begin to carve out your identity and nail down your interests, you can then begin to search for schools that cater to them. Google searches are a good start to find out what programs are best suited for you. Just as useful, however, is to look to the critics you are using in class and their contemporaries. Another option, and one I utilized in earnest, was to ask my professors about their own experiences and those of their friends/colleagues at their respective institutions. These informed, personal perspectives can be far more illuminating than the sanitized portraits (or, as I like to say, the please-give-us-your-money versions) found on school websites and promotional material.

Keep in mind that applying to grad school can be expensive, so unless you manage to acquire application fee waivers (obtained, for instance, by attending a school’s open house), consider limiting your selections to a narrow list of places you could really see yourself attending. I had a finalized list of five schools, about the recommended average, by mid-fall semester of my senior year.

4. Take the GRE.

I’ll be honest: I think standardized tests are bogus and not at all indicative of one’s potential as a student. Though many schools are moving away from requiring them with their applications, many still utilize the GRE, or the Graduate Records Examination. Taking the GRE may be in your best interest to not limit the schools to which you can apply.

The GRE tests on analytical writing, quantitative reasoning, and verbal reasoning. I hadn’t touched the sort of math found in the quantitative reasoning portion since high school. So I had to brush up ahead of time. Like most standardized tests, once you learn the structure of questions, you have a stronger chance of performing well. There are many online resources available to sharpen your familiarity of the test, and you can certainly purchase the official GRE book (the Learning Resource Network on campus also has some available).

If you aren’t too thrilled about your results, take heart. If you are applying for a program in the Liberal Arts, most schools don’t put much weight on your quantitative reasoning score. You can also take the GRE every 21 days, up to five times within a year, until you are satisfied.

5. Get your recommendation letters.

Though the exact requirements for an application vary from program to program, most schools, regardless of discipline, will ask for recommendation letters. It is best to approach a person who knows you in an academic context, but ideally your recommender should know you as more than a name on their attendance sheet. Perhaps you have had them for class multiple times or they know you outside the classroom by being a sponsor of a campus organization. Regardless, it may help you to schedule an appointment to sit down with any potential recommenders and outline what your intentions are with graduate school: what you plan to study, what your career goals are, what related activities you do outside the classroom, etc. This not only reminds them of what you accomplished in their class, but it allows the recommender to tailor the letter to best serve your specific needs. In respect of their time, it is best to ask well in advance, preferably as early as the beginning of the semester.

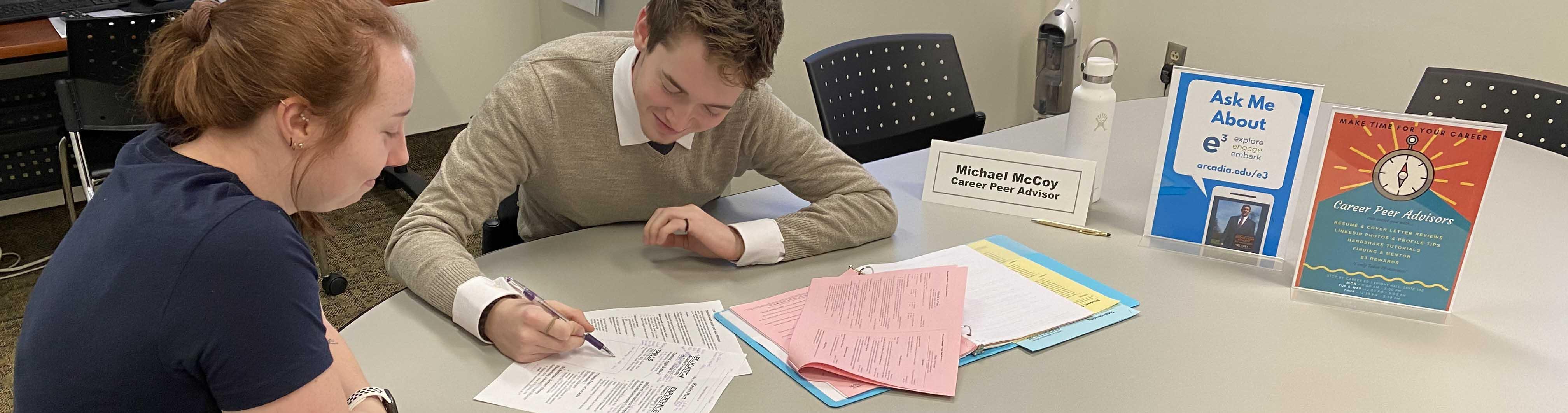

A Writing Center consultation in progress!

6. Gather your remaining materials (and don’t be afraid to ask for help!).

Besides recommendation letters and GRE scores, my applications generally required a writing sample between 10-25 pages, a resume/curriculum vitae, and a personal statement. With regards to the writing sample, it is important to select a piece that you feel is emblematic of your identity as a scholar. I chose to use my thesis. Though it was longer than the recommended page limit, I sent along an excerpt with an author’s note to demonstrate that I was already working on longer, more graduate-level type work.

The personal statement is usually 1-3 pages and tends to ask you to describe your preparation, goals, and motivation for your graduate course of study. The tremendous discomfort of writing about oneself notwithstanding, the narrow page limit can be difficult to navigate. As a result, it can be easy in this section to fall back on platitudes or cliches of destiny and passion. But the more defined your focus, the better. You should not only be painting yourself as the ideal master’s student, but the ideal master’s student for that particular institution, taking the opportunity to demonstrate the research you’ve done on their program. For example, if a school boasts a master’s program that has a heavy emphasis on giving students first-hand teaching experience, write about your time as a tutor and how this has readily prepared you to work with students and has you interested in that part of their curriculum.

Don’t be too proud to reach out to others for help or for a second set of eyes. It is not a sign of inadequacy or an admittance that you cannot do it independently. If anything, it is smart to take advantage of the resources around you. Ask a professor or peer if they would be willing to look over your personal statement or writing sample. The Writing Center is always an option. The Office of Career Education also holds Grad School Advising sessions for students regardless of where they are in the process, as well as one-one-one workshops with a career educator to fine-tune resumes and personal statements.

7. (Try to) relax.

After sending out all your applications, it can be easy to slip in a sense of purgatory, wringing your hands over what you could have done better as you wait anxiously for results. It is difficult being in the dark about a major life event. But try not to drive yourself wild with what-ifs. While avoidance is normally not good advice, in this particular case it’s the perfect time to distract yourself with your preferred brand of deflection. What better time to catch up on that Netflix series you’ve been putting off? You did a lot of work. Take the break you deserve!