It is the middle of a lacrosse game in late April when the Stevenson girl I’m defending starts talking to me about her plans for after the game, her desires to study abroad, her opinion of the men’s lacrosse players heckling from across the stadium. Though conversations may happen on the field, there is usually a level of decorum in collegiate competition that invokes a sense of focus and gravity. But when there’s a 10 point (and growing) differential between the score, my complete demoralization is just a minor impediment from her reaching the weekend.

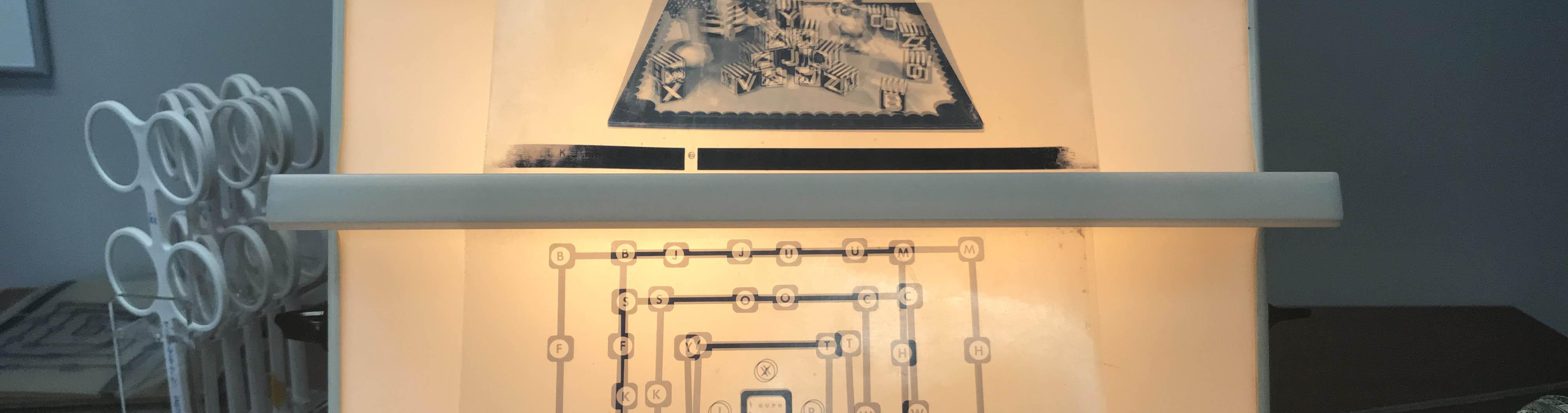

Lens tool called a flipper and practice images used during vision therapy.

The ball is moving toward my end of the field, where it’s been for the majority of the game. “Hold that thought,” I tell her. “I have to play lacrosse real quick.”

From the left, a girl in bright Stevenson white makes a breakaway to the net. I move to the other side of the cage, extending my stick far in front of my body, hoping to simultaneously impede her drive and remain out of shooting space. The next thing I know, there’s a girl cutting from behind the net. I am not even aware of her presence until her shoulder, elbow, head—I’m still not completely sure—makes hard contact with my left temple, snapping my head back. We both crumple to the ground, but I quickly get back to my feet.

“Are you okay?” my teammate Kirsten asks.

An intense pressure rushes to my brain. It feels as though massive fingers have wrapped themselves around my skull.

“Yeah,” I say, absently. “Never better. Do I get the ball?”

In the days following, I felt as though I were wading through honey, the world moving around me slow and syrupy. I remember sitting across from my professor, Matt, and watching his mouth form words, but with the way I was retaining information, he might as well have been speaking French. As a result, I asked him to repeat himself more than enough times to be annoying. The rest of my human interactions tended to go in a similar fashion— me feeling every bit underwater while trying to convince the other person (and myself) that I was firmly rooted on dry land.

At first, I refused to confront that there was something wrong with me. Perhaps I was dehydrated. Had allergies. Was just a big stinking drama queen. There was simply no time in my schedule for a brain injury, especially with finals on the horizon.

But after squeezing in the last lacrosse game of the season (which was irresponsible and potentially dangerous, and I do not recommend), a meeting with Arcadia’s head athletic trainer confirmed what I tried so hard to avoid. I left her office with papers to hand my teachers saying that I was under observation for concussion symptoms. Even though I had what most people would consider a legitimate excuse to take it easy, I was nervous to inform my professors of my situation.

I found my fears to be in vain. They were nothing but supportive, sympathetic, and most importantly, willing to accommodate me to the best of their abilities. I was able to get deadlines of papers and tests pushed back in order to give my brain a much needed break.

I found my fears to be in vain. They were nothing but supportive, sympathetic, and most importantly, willing to accommodate me to the best of their abilities.

– Jess Derr

Still, I couldn’t focus on healing until I got my academic obligations out of the way. The results were mixed, to say the least. I wore sunglasses during my British Literature final. There’s a paper on Light in August that I barely remember writing. Somehow, I clawed myself to the finish line with my GPA in tact.

Though I thought things would change for the better with school conquered, my gaggle of doctors and therapists taught me this: Brains are fickle and respond differently to trauma. There is no set timeline, presentation of symptoms, or singular treatment. Whereas someone else with a concussion may be sensitive to sound, I was able to go to a Broadway show and a Hozier concert. My triggers were visual: reading, driving, screens—even shopping in stores with bright lights and a lot of stimuli were enough to make me feel like I was on a boat. While some people heal in a matter of days or weeks, I still encounter symptoms nearly seven months later.

Most people still believe that concussions are healed by sitting alone in a dark room. I quickly learned that this was not the case. Once the athletic training staff at Arcadia determined my symptoms were not improving on my own, they sent me to a nearby vestibular therapist. The vestibular system, a sensory complex in the inner ear, helps with balance, spatial orientation, and the stabilization of images during head movements. Some exercises included sitting on a yoga ball and switching my sight from three interspaced buttons along a string; staring at a point on the wall while standing on a balance board and shaking my head; and watching videos that had me work on tracking moving objects.

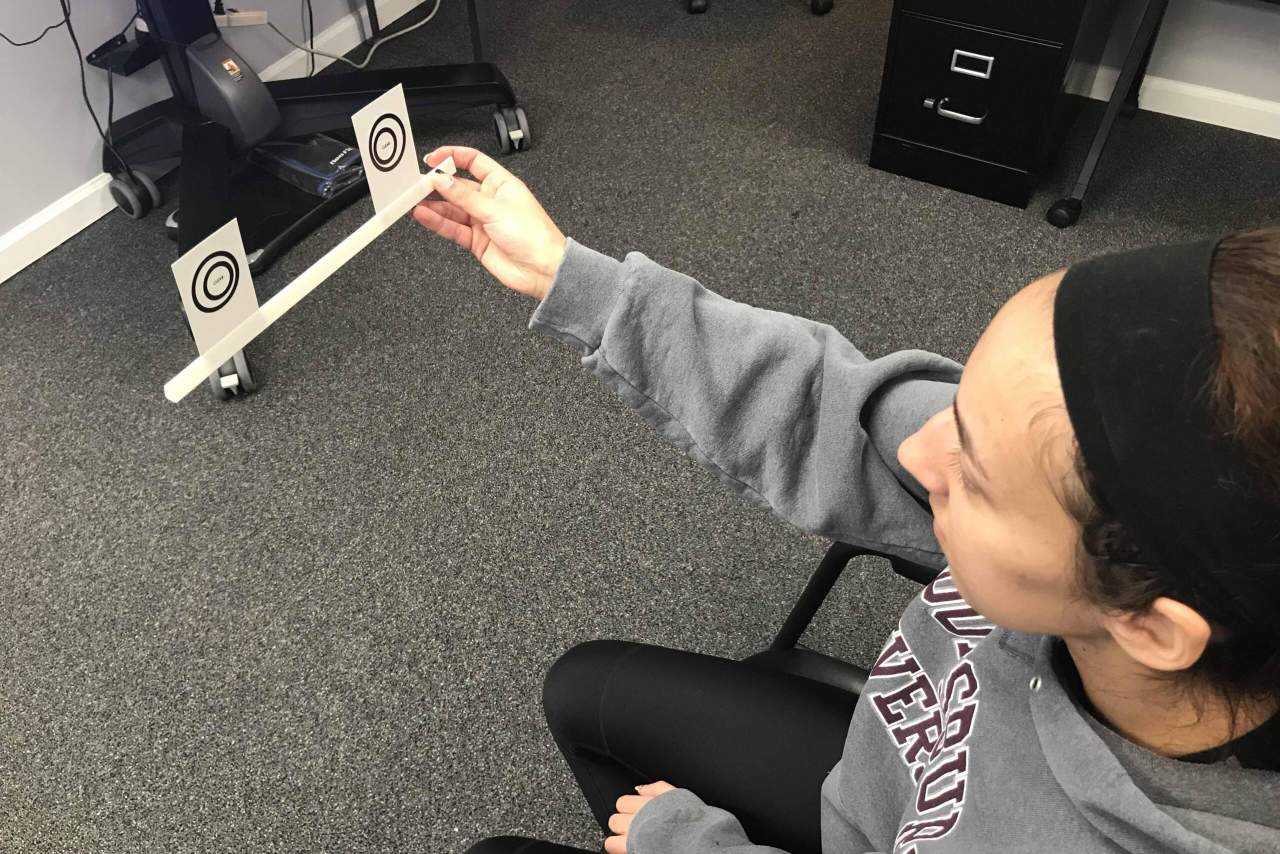

Unfortunately, after three months of vestibular therapy, though I was improving, my progress was not where it should have been. I was sent to an ocular specialist at Tru Vision Therapy, where it was determined that the muscles in my eyes were not working properly. The result was convergence insufficiency, where a person is unable to sufficiently bring the eyes inward while doing close work like reading. As the eyes drift out, the body exerts additional effort to turn the eyes in, resulting in strain and nausea.

In vision therapy, I work with two great therapists, Tonya and James, who put me through exercises that may seem menial to the casual onlooker, but make my eyes feel like they’ve just had to compete in the CrossFit Games. They use specific lenses, prisms, and filters, along with specialized instruments and computer software, to train my eyes to properly converge and diverge. As of now, I’m about halfway through therapy and am definitely seeing improvement.

Exercise used for practicing eye convergence by forcing one’s eyes to make a third circle in between the two visible on the tool.

Before this experience, I had no idea what vestibular or vision therapy would entail, thinking that I would have cathodes taped to my head to administer electric shocks like Eleven in Stranger Things. People are often reticent to talk or learn about emotional effects that come with post-concussion syndrome. Concussions can be miserable and isolating. In the early summer months, my days bled together in their monotony. I had little to look forward to beside my next meal and going back to bed, and even then I had to take sleeping supplements because my headaches were so intense. My usual sources of stress relief—reading, writing, watching television, playing video games—were the things that made me the most physically ill. I felt every bit a vegetable, a prisoner in my own body. I became increasingly depressed thinking that I’d never be as sharp as I once was or that I’d never go a day without a headache again.

Part of me still hates that on some occasions I have to explain why I seem unfocused or reserved. It seems like an admittance of inadequacy. Most people are understanding enough, but I have experienced the stray individual who makes a face and asks, “You’re still dealing with that?” There is no magical formula for healing. The timeline is messy and inconsistent. I had to learn to cherish the times of reprieve and roll with the bad days.

And though I am finally seeing light at the end of the tunnel, I still get my share of bad days. Being a senior year English major is not exactly easy on the eyes. If I’m not squinting over a book, I’m glued to a computer screen. There are times where I have to slow down and prioritize pain management over academic productivity. But I am thankful that I have had such a supportive circle of friends, family, and Arcadia faculty as I continue along the path to recovery.